It’s a long way from Varanasi, a holy city on the Ganges River in northern India, to the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (Cimmyt) in Texcoco, México state.

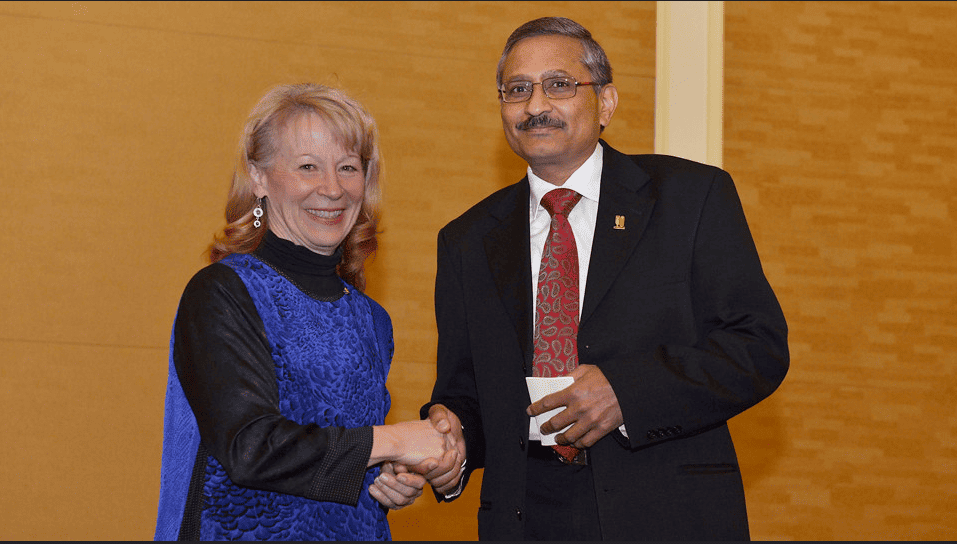

But the vast distance between the two points was no barrier to a career at Cimmyt for Ravi Singh, a distinguished scientist who grew up in Varanasi but spent most of his working life at the renowned research organization and rose to become its head of global wheat improvement, a position he held for almost two decades before his recent retirement.

Singh — who received a multitude of awards during his long wheat-focused career, including the highest honor conferred by the Government of India to nonresident Indians — recently spoke to Mexico News Daily about his life and work in Mexico, his home since 1983.

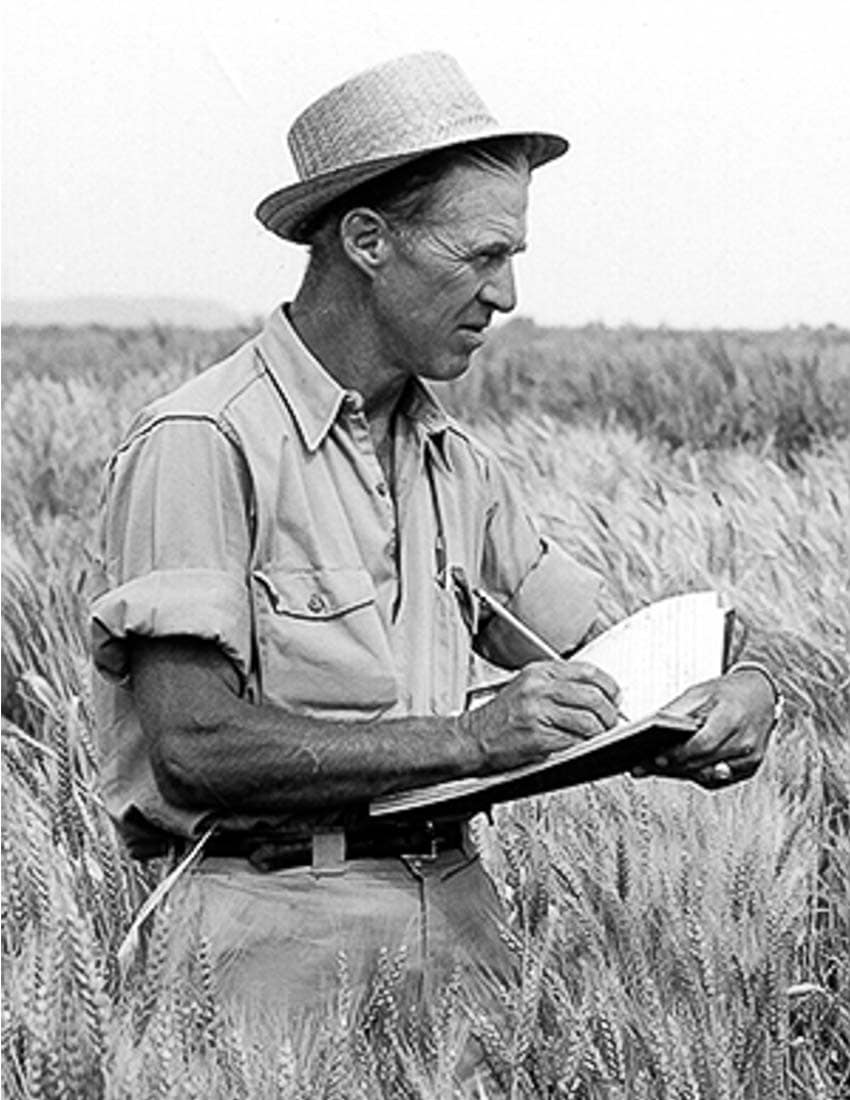

After completing a PhD in agricultural genetics and biometry at Australia’s University of Sydney, he was offered a postdoctoral fellowship at Cimmyt, which developed in its early years under the leadership of prominent United States agronomist Norman Borlaug, a Nobel Peace Prize winner considered the father of the Green Revolution.

Singh accepted the offer and thus, as a young man, found himself working on the outskirts of the capital of a country where corn — not wheat — is most definitely king. Undeterred, the new doctor in agricultural genetics embarked on a career largely dedicated to the study of wheat, a crop thought to have first been cultivated more than 10,000 years ago in the Fertile Crescent, a region spanning several modern-day Middle Eastern countries, including Iraq, Israel, Jordan and Lebanon.

In Texcoco, Singh had the opportunity to build on the work of Borlaug and other agronomists and scientists and put his mind to a noble aim he had thought about since he was a boy lining up at ration shops in India: how to grow enough food to ensure that no one in the world goes hungry.

To that end, much of his work in Mexico focused on developing new wheat varieties that would thrive in different climatic conditions around the world and produce large crop yields as a result. Singh was certainly prolific in that regard: he contributed to the development, release and cultivation of over 700 wheat varieties in the 37 years he spent at Cimmyt.

“Even though you are in Mexico, you can generate very competitive materials for geographies like Australia, Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Pakistan, … the Ethiopian highlands, … even Nigeria,” Singh told MND, referring to wheat varieties that not only produce large yields but are also endowed with resistance to deadly disease pathogens, particularly those that cause different kinds of rust diseases in wheat.

“By continuously providing superior varieties, we increased wheat production and incomes of millions of smallholder farming families,” he said in a previous interview after winning the prestigious Pravasi Bharatiya Samman Award, the top Indian government award for Indians who live abroad.

Speaking to MND, Singh highlighted that Cimmyt is a nonprofit research organization and thus “gives away” seeds for new wheat varieties and provides free access to the associated techniques and knowledge it develops. “We’re not in the seed business,” Singh emphasized.

Over the past four decades, Singh’s work has had a significant impact around the world — in Asia, in Africa and in Latin America, including in his adopted homeland, where wheat is an important crop albeit one that is not grown anywhere near as widely as corn.

He told MND that farmers in Mexico have long been receptive to the expertise he and other Cimmyt scientists share with them, noting that the wheat growers he met in Sonora — the country’s biggest wheat-producing state — during his early days in Mexico “were always looking for new technologies to improve their profitability [and] sustainability.”

Mexican farmers’ openness to sowing new wheat varieties and trialing emerging agricultural technologies made Mexico a good place to work for a scientist such as Singh, who four decades after moving here feels very much at home.

Food security

Singh told MND he is optimistic about humanity’s capacity to produce enough food for a growing global population, but cited a range of things he believes could soon pose a threat to food security.

They include climate change, seed shortages, insufficient government investment in agriculture and water infrastructure and a lack of capacity to store grains.

“In several countries, people think that the private sector is going to resolve all the problems, and that’s not the case,” said Singh, who also worked as an academic supervisor, authored hundreds of journal articles and is among the world’s top 100 plant science and agronomy scientists as listed by research.com.

“There is still a lot of need for the public sector to be engaged in agriculture,” and many countries around the world require additional capacity to store grain, he said.

Singh acknowledged that the current Mexican government has invested in agriculture and water infrastructure, but stressed that a lot more investment is needed, and that investment decisions need to be proactive rather than reactive.

Norman Borlaug and the Green Revolution

According to the International Encyclopedia of Human Geography, “the Green Revolution is the term given to the use of high-yielding varieties (HYVs) of wheat and rice particularly during the 1960s to increase food crop production, especially in India.”

“The new seed varieties, popularly called ‘miracle’ seeds, were developed in Mexico (wheat) and the Philippines (rice), but it was the new dwarf varieties of wheat [developed by Norman Borlaug and others] which provided the bigger growth in yields per hectare,” the summary continues.

Mexico — and specifically the Yaqui Valley in Sonora where Borlaug introduced new wheat varieties in the middle of last century — is considered the birthplace of the Green Revolution.

While Borlaug has been described as “history’s greatest human being” and credited with saving “1 billion people from death by starvation,” the Green Revolution of which he was a key leader has also been criticized for a range of reasons, including for some negative impacts it had on the environment and water resources.

“Critics blame debt, displacement and ongoing malnutrition in India and elsewhere on a revolution they say was anything but green,” The Washington Post reported in 2020

Singh acknowledged that the Green Revolution is controversial, but emphasized the positive impact it had at a time when food insecurity was a major concern.

“It depends how you want to see it,” he said. “The Green Revolution provided food instead of letting people die,” Singh said.

In Mexico, the Green Revolution allowed Mexico to quickly become self-sufficient for wheat.

“In 1943, Mexico imported half its wheat, but by 1956, the Green Revolution had made Mexico self-sufficient, and by 1964, Mexico exported half a million tons of wheat,” according to Global Food Security, a United Kingdom cross-government program on food security research.

Over the past four decades, Singh contributed to the development of 68 wheat varieties released in Mexico in collaboration with the National Institute for Forestry, Agriculture and Livestock Research and other Mexican government institutions.

Mexico’s most widely grown bread and pasta wheat varieties were both developed by Singh’s team at Cimmyt. Mexican wheat varieties developed in Texcoco are also widely grown in India and many other countries, a testament to their proven capacity to produce large yields and resist disease.

New technologies in agriculture

Acknowledging that it will be a challenge to grow enough food for a global population that is projected to reach 10 billion in the second half of this century, Singh emphasized the need for people to accept the use of new technologies and techniques in farming.

“People will need to trust new [agriculture] technologies. … We need to be open-minded,” he said, noting that there is a general acceptance of new technologies in other fields such as medicine and manufacturing.

Concerning the cultivation and consumption of genetically modified crops — a particularly controversial topic in Mexico and North America — he suggested people shouldn’t only focus on the alleged cons of growing and eating GM food.

“You have to see what’s good about it before you straight-out reject it,” he said, highlighting that GM crops require less pesticide than their non-GM counterparts.

The lighter side of working in Mexico

Singh recalled some amusing experiences from his early days in Mexico when his Spanish was still very much a work in progress. He told MND that the first thing some of his “colleagues in the field” tried to teach him while he was working on farms near Ciudad Obregón, Sonora, was precisely “not what you should be learning.”

Nevertheless, Singh found value in the swearing and slang lessons he received, explaining that he saw them as an opportunity to learn what not to say in polite company.

“But then if by mistake you say [one of the bad words] everyone laughs. You need to be very cautious!” he said, before noting how such interactions with his Mexican colleagues in fact helped to build camaraderie.

Life in Mexico

Singh said that the friendliness of the Mexican people has been a constant throughout the 40 years he has lived in Mexico, and noted that he has developed strong bonds with colleagues, friends and neighbors during that time.

He has observed many changes in Mexico since he moved here in the early 1980s, describing his adopted homeland as a constantly “evolving” country. He also remarked that the Indian community in the greater Mexico City area has grown considerably over the same period.

In his initial years in Mexico, Singh recalled gathering with “just five or six [Indian] families” for cultural celebrations such as Diwali and Holi, whereas he recently attended an event at the Indian Embassy alongside hundreds of his compatriots.

“I met people there who I had never met before,” Singh said after acknowledging that the Indian community in Mexico is now “huge.”

In his own words: Singh explains the process of selecting a variety in the CIMMYT wheat breeding program.

While he’s now retired from his position as head of global wheat improvement at Cimmyt, he remains a senior advisor for the research center and continues to share his vast knowledge with farmers in Mexico and those abroad in countries such as China and his native India.

Singh told MND that he would visit both Asian countries during wheat harvests in the first half of this year to observe firsthand the results of the latest growing seasons and hear about the challenges farmers face.

But as much as he likes to travel, the acclaimed wheat geneticist and breeder is always happy to return to Mexico, where he has now lived for more than half his life.

Mexico today, “just feels like it’s my home — that’s it!” Singh said.

By Mexico News Daily chief staff writer Peter Davies ([email protected])