In the pre-dawn silence on Oct. 27, a hushed group of armed men exploited the shroud of darkness to steal toward the Chin Shwe Haw Bridge in northern Shan State on Myanmar’s border with China. At the military outpost near the bridge a security guard nodded drowsily, unaware of the looming danger. A sudden burst of automatic rifle fire, followed by mortar explosions, announced a surprise attack by the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA), a Kokang rebel group intent on taking control of a major portal for Myanmar’s cross-border trade with China. But the MNDAA was not alone in attacking the military regime’s positions on Oct. 27, nor was Chin Shwe Haw Bridge the only target of the assault.

In fact, the MNDAA attack was just the opening salvo in a coordinated strategy developed over the past year by major armed elements of Myanmar’s anti-coup movement to mount a 360-degree assault on the military from east to west, and from north to south. The Myanmar generals’ decades-old military strategy of keeping the country’s various ethnic armed groups engaged in separate battles with the army—and, at times, with each other—has finally been countered.

The first of a two-part series, this piece will lay out the current state of the battlefield in Myanmar as shaped by Operation 1027. The second part, to follow shortly, will analyze the implications of the expanding conflict and the challenges that lie ahead.

Coordination and preparation

Despite various claims that China has played a key role in Operation 1027, in support of its goal of eliminating scam centers in Kokang that prey on Chinese citizens, in reality this was not the driving factor. Rather, the offensive we are seeing is the beginning of a coordinated strategy developed over the past year among key resistance groups with the aim of engaging the military of the State Administration Council (SAC, as the junta calls itself) on all fronts. Observers closely monitoring the post-coup conflict were probably aware that the anti-coup movement had formed several coordinating mechanisms for conducting the ground battle against the military, namely, the Central Command and Coordination Committee (C3C) and Joint Command and Coordination (J2C), formed to coordinate the work of the PDFs and allied ethnic armed organizations (EAOs). The civilian National Unity Government (NUG) also formed an Alliance Relations Committee (ARC) to liaise with ethnic armed groups that had remained nominally independent, including the Brotherhood Alliance between the MNDAA, the Arakan Army (AA) and the Ta’ang National Liberation Army (TNLA). From mid-2022, NUG ARC members met frequently with the Brotherhood Alliance, which was providing military training to PDFs and other armed groups with common goals.

Negotiations for a joint military strategy between the NUG and the Brotherhood Alliance appear to have commenced in earnest in early 2023, when the Brotherhood Alliance members began openly disclosing information about their support for resistance groups. According to insider sources, NUG Minister of Defense U Yee Mon visited the northern part of the country to engage directly with the Brotherhood Alliance for several months on a coordinated strategy. Other resistance groups, such as the Burma People’s Liberation Army (BPLA) and People’s Liberation Army (PLA), which received military training from the Brotherhood Alliance, played key roles in aligning the strategic objectives of the alliance with the anti-coup resistance movement.

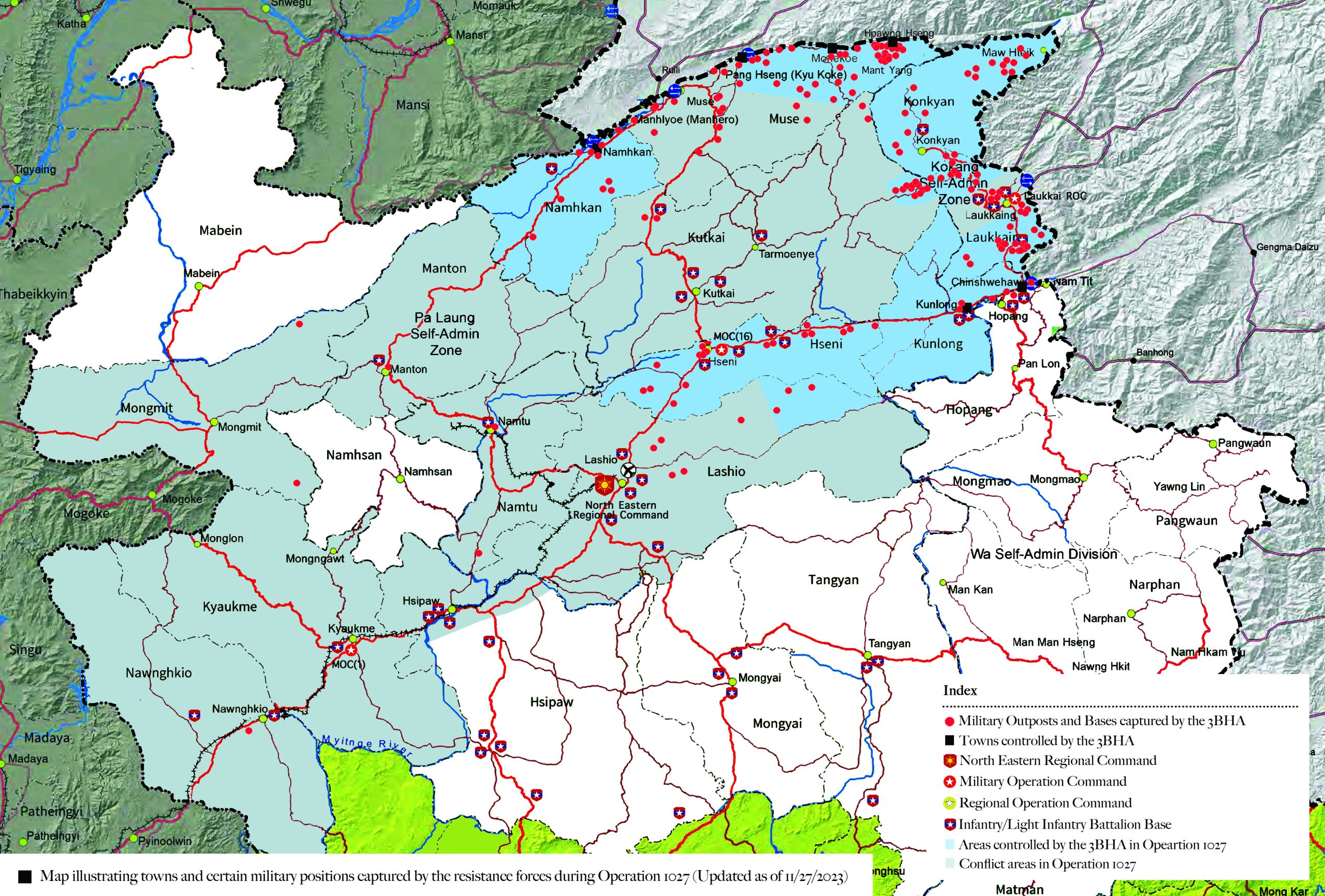

Preparation for Operation 1027 began a year ahead of time, when the MNDAA formed and equipped a new military brigade known as Brigade 611 composed of soldiers from diverse ethnicities, including Bamar, and diverse groups such as the AA, NUG PDFs, Karenni National Defense Forces (KNDF), BPLA, PLA and others, all under the command of the MNDAA. Brigade 611 was deployed primarily between Lashio and Muse and Lashio and Chin Shwe Haw/Laukkai in order to block the military’s strategic routes to Kokang on the border with China. Drone experts from resistance groups in other areas had also been present in Shan State since 2022.

Without explicitly analyzing the progress of the post-coup military trend, some readily concluded that Operation 1027 is not a coordinated attack, but primarily driven by the Brotherhood Alliance without prior consultation with the NUG. The extent of the coordination, however, was clearly revealed by the general secretary of the TNLA when he admitted to extensive consultations with the NUG and the inclusion of forces under the command of the NUG Ministry of Defense in Operation 1027, making clear that the offensive was not a spontaneous event, but emerged from year-long preparations coordinated with the broader resistance movement.

Operation 1027

The attack on the military stronghold in Kokang on the Chinese border, code-named Operation 1027 for the date it began, was led by the Brotherhood Alliance in coordination with a number of other resistance forces. The assault on Chin Shwe Haw was followed quickly by attacks on Kunlong, Mongko, Lashio, Hopang and Namkham along Myanmar’s border with China. Within weeks, the alliance managed to capture over 200 military positions, including strategically significant bases in these towns and beyond, effectively closing the border to trade between the two countries.

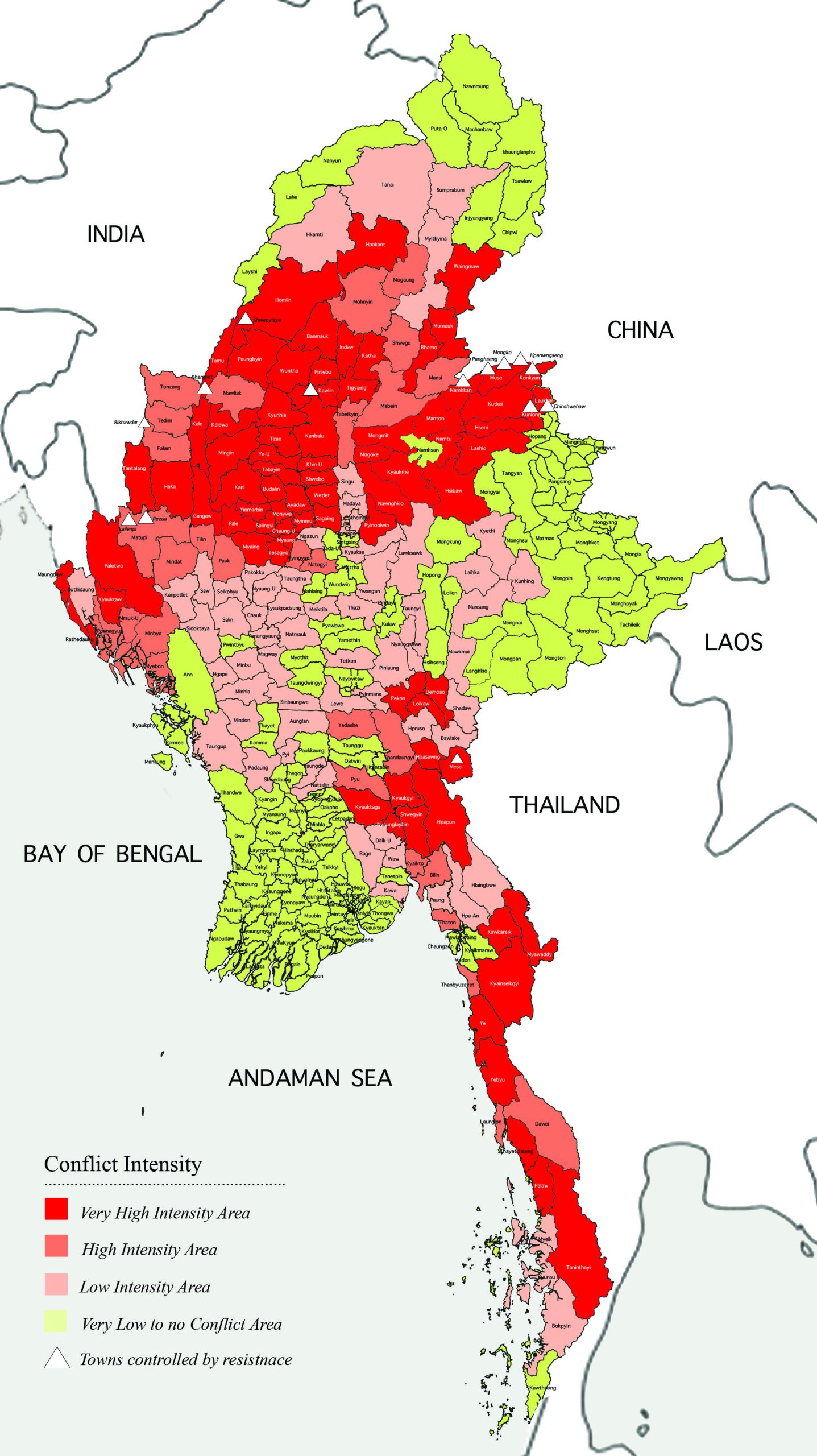

A month after the launch of Operation 1027, the Brotherhood Alliance declared that the operation had evolved to the next phase: a nationwide battle against the military. Other ethnic armed groups along with PDFs were attacking military encampments in Kachin State to the north, Sagaing, Magwe and Bago regions in the country’s heartland, Chin and Rakhine states in the west, Karenni (Kayah) in the east, and Karen State and Tanintharyi Region to the south. For the first time in history, the military now faces simultaneous attacks from armed resistance of various types, ranging from conventional warfare to guerrilla tactics and from overt to covert operations, in 12 out of Myanmar’s 14 states and regions. The evidence of a coordinated nationwide offensive by the combined forces opposing the hapless coup regime has become unmistakable.

Resistance offensives cascade nationwide

Penetration into Mandalay: The first group to take advantage of the opportunity created by Operation 1027 was the Mandalay PDF under the command of the NUG, with seven battalions trained and equipped by the TNLA since 2021. Operating mainly in northern Shan State’s Kyaukme and Nawnghkio areas, they aimed to occupy Mandalay Region from the east. They joined forces with the TNLA in Operation 1027 to attack military positions in their areas of operation and block military reinforcements to northern Shan State, while at the same time penetrating their target areas in Mandalay.

While continuing to block military access along the Lashio-Mandalay highway to northern Shan State, Mandalay PDF has begun infiltrating parts of Mandalay Region heavily defended by the military, in Madaya. Recently the PDF announced its “Shwe Pyi Soe Operation” with the ambition of occupying Mandalay.

Karen: On the day Operation 1027 commenced, the forces of the Karen National Liberation Army (KNLA) and PDFs initiated attacks on Kawkareik in Karen State. With limited weaponry and ammunition in southern areas compared to the north, resistance forces have not aimed to seize towns and major military bases. Instead, they have encircled towns, dominated key supply routes, and cut off military supply and reinforcement. While not declaring the seizure of towns, the resistance forces in Karen and Tanintharyi regions have nonetheless gained substantial control over towns and neighboring areas, such as Kawkareik and Hpapun, as well as dominating strategic routes, such as the Kawkareik-Myawaddy and Ye-Dawei highways. Despite slow progress, the KNLA is unlikely to forgo the opportunity to advance its military gains amidst the chaos engulfing the military.

Bago: Also in the southern theater, the KNLA and PDFs have persistently sought to infiltrate Bago Region, crossing the Sittaung River. The military has established three defense lines to thwart the advance of resistance forces into Bago areas, but despite attacks by the Sit-Tat (Myanmar’s military), the resistance forces have successfully outmaneuvered the military’s heavy air strikes and artillery to penetrate the second line of defense, operating freely between the old Yangon-Mandalay highway and the Sittaung River, giving them the the potential to threaten, and cut off from one another, Yangon and Naypyitaw cities. Despite a robust and heavily fortified military defense between the old and new highways between Yangon and Naypyitaw, resistance forces now appear poised for escalating attacks in that region soon, aligning with Operation 1027.

Kachin: Prior to Operation 1027, the SAC military had escalated its offensive against the Kachin Independence Army (KIA) to interdict KIA supply and assistance to PDFs in the north. When the outbreak of Operation 1027 compelled the military to redirect its limited resources to the new conflict areas, the KIA moved on the military base at Mongton in northern Shan State and a base on the Gangdau-Bhamo Road on Oct. 31, while continuing its military offensives in upper Sagaing Region.

Sagaing and Magwe: On Nov. 2 and 3, NUG PDFs, collaborating with local defense forces and allied EAOs, executed coordinated attacks on military positions, police stations and prison camps in Sagaing and Magwe, complementing Operation 1027. On Nov. 6, the NUG Ministry of Defense announced it had control over Kawlin in upper Sagaing, and on Nov. 7, over Khampet on the Indian border. If resistance forces manage to take Tamu together with Khampet, it would give them complete control of the Kabaw Valley on the Indian border. They are also aiming to consolidate control of the “3 Ks” area (Kawlin, Katha and Kantbalu), where they have already established strongholds in most rural areas, but not yet all military bases. From here, the coordinated resistance is likely to focus on seizing urban areas and key military bases in the heartland.

Chin: On Oct. 30, the Chin National Front (CNF) announced that it would follow the lead of Operation 1027 to confront the military in several regions of Chin State. On Nov. 7, Chin resistance forces managed to seize Rihkwanda, a town bordering India, and they have proceeded to capture military bases and more towns such as Lailenpi and Rezua in Matupi. The mountainous terrain and remoteness of Chin State has presented significant challenges to the military, giving the resistance movement greater license to gain control over the state, encircling and isolating heavily defended military bases. The momentum against the military in other areas of the country will only strengthen the CNF’s advantage.

Rakhine: On Nov. 13, the powerful Arakan Army, having achieved victories over the military on the Chinese border as a member of the Brotherhood Alliance, began to launch offensives on military positions in Rakhine State on Myanmar’s western border with Bangladesh, marking the end of a year-long ceasefire in that state. Focusing its attacks on police and military posts on the border, the AA has successfully captured several outposts in Rathedaung and Maungdaw, a strategy that seems designed to open gateways to the neighboring countries of Bangladesh and India for access to food for the Rakhine population, in order to foil the predictable military blockades of access routes inside Rakhine. AA operations are already expanding rapidly to other parts of Rakhine and Chin states, with recent escalations in fighting in Pauktaw, Myebon and Paletwa.

Karenni: To the south of Shan State, Operation 1027 also ignited the combined Karenni resistance forces, comprising the Karenni Army (KA), Karenni National Liberation Front (KNLF), Karenni National Defense Forces (KNDF), PDFs and other allied groups, to commence operations against the military, initially achieving full control of Mese on the Thai border. On Nov. 11, they announced Operation 11.11 aimed at completing the capture of Loikaw, the Karenni capital located only 110 km or so from the Myanmar capital of Naypyitaw, which would give the resistance easy access to the junta’s power base. Karenni forces’ capture of military positions in Loikaw, Demoso and Mobye has compelled the junta to allocate its dwindling resources to the defense of Loikaw, preventing a large-scale redeployment to northern Shan State in response to Operation 1027. With its ground troops in Karenni defecting in large numbers and refusing to fight, the junta is now pounding Loikaw with aerial assaults, causing mass population movements into Shan State and across the Thai border. Although the Karenni forces have not yet achieved full control of Loikaw, they continue to make steady progress. Because of its strategic location, the seizure of Loikaw could alter the entire dynamic of the post-coup conflict.

Analysis of the nationwide conflict triggered by Operation 1027 reveals three key observations. First, the operations across different theaters are interconnected. Second, the synchronized 360-degree attack on the military from many locations around the country provides unmistakable evidence of a substantial degree of prior coordination among the resistance forces. And third, the SAC military must now concentrate its remaining limited resources in a few key conflict theaters.

History may one day conclude that the military coup of February 2021 proved fatal to the Myanmar military’s decades-long monopoly on power by energizing the country’s wide array of non-state armed groups to at last find common cause in bringing down the military dictatorship that has plagued the population for so long. However, the battle is not over, and many challenges still lie ahead for the anti-coup movement.

Ye Myo Hein is a global fellow at the Wilson Center based in Washington DC. The views expressed here are his own and may not reflect those of the center or the US government.