But the story of China’s quest for a home-grown jet continues at the production facility nearby, where units of the C919 – the Y-10’s spiritual descendant – roll off the line. More than 30 years after funding constraints and design flaws clipped the wings of the Y-10, a new generation of airliners is bringing a decades-long ambition into reach.

But this auspicious start, from domestic certification to the beginning of commercial operations, is likely to be the easiest leg of a long journey to international relevance.

“Comac has a lot of convincing to do,” said Li Hanming, an aviation analyst and founder of a transport consultancy which operates in the United States.

“The best way to showcase the C919’s virtues and viability for the global aviation industry is to let Chinese airlines run it well.”

A domestic success story

For Beijing, the C919 is a totemic project, a source of patriotic pride and a demonstration of China’s advancement in technologically advanced research and manufacturing.

“In the past, some said the best choice for us is to rent [passenger aircraft] from others, and that the last option is to make our own,” Xi said. “But we have reversed this notion.”

The next decade saw more than 100,000 engineers and workers brought together to work on the C919. They came from 36 tertiary institutions and 200 businesses across China, with total investment reaching hundreds of billions of yuan.

Political significance aside, Beijing’s dogged pursuit of its own airliner also makes commercial sense, as it can leverage its enormous market and state capacity to ensure the C919 gets off the ground.

More than one-fifth of the world’s new planes will fly in Chinese airspace between now and 2041, Beijing-based Cinda Securities noted in a report last year. New plane demand from the world’s second-largest economy will hit 9,284 during that time, worth about US$1.47 trillion.

Comac’s own estimates put the country’s demand for narrowbody jets between now and 2041 at 6,288, a supply with a potential US$749.3 billion in value.

The race for overseas approval

To expand on its domestic success, Comac has embarked on a quest for international adoption, with work ongoing to obtain airworthiness certification for the C919 from the European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA).

“We have aimed for 2025 to get the all-clear from EASA,” said an optimistic Jie Yuwen during a media tour earlier this month.

We are confident the plane, having been certified to fly in China, is also safe to fly elsewhere

Gu Xin, director of the centre, also confirmed the 2025 timeline.

“We very much look forward to certification next year. We are working hard, as this requires cooperation from both sides,” Gu said.

“Certification from EASA means identifying [if] there is any safety problem with the C919 and put everything on the table for discussion,” he said. “We are confident the plane, having been certified to fly in China, is also safe to fly elsewhere.”

Gu added he and his colleagues had meticulously reviewed more than 6,100 reports related to the C919’s domestic certification.

The goal of certification by 2025 is an ambitious one – perhaps too ambitious, some industry observers said.

Mayur Patel, head of Asia for OAG Aviation, a global air travel data provider based in Singapore, said the EU’s certification process is stringent.

“It could be a bit optimistic to expect the all-clear any time soon, but I would be cautiously optimistic that the C919 will ultimately be certified [by EASA],” he said.

Li, the aviation analyst, said Comac needs to assure the EU it benchmarked C919’s safety performance and redundancy systems against internationally recognised standards for the plane’s domestic certification.

“I’d say the EU’s validation can be granted in around 2026 if EASA is satisfied that CAAC adopted the same rules – so the Europeans won’t need to do all the tests themselves – and if there is trust and good communication,” Li said.

“EASA is watching closely to see how well the C919 is faring in daily operations with airlines in China.”

But recent reports suggest the C919 is still under a cloud of suspicion.

Citing EASA, Reuters said the Chinese jet is “too new” to be approved by 2026 and that the EU watchdog will take “whatever time is needed” to give the airliner the go-ahead.

“Comac still hopes for 2025 certification, but there are some discrepancies in standards and methodology between CAAC and EASA,” Jie said.

He revealed that China does not have equivalent rules to Europe regarding supercooled water droplets, volcanic clouds and new design elements that identify, compile and mitigate human errors – but added CAAC is updating its safety protocols to include them.

“Comac may need to tweak or optimise the C919’s design accordingly, and that may entail more time and communication with EASA,” Jie said.

Stressing that aviation administrations in China, the EU and US adopt similar standards, Gu argued that EASA will have no reason to defer approval if it cannot find an issue.

“There are overlapping general provisions and assessment criteria in the three jurisdictions,” he said. “Our standards are not that dissimilar to those in the West.”

Making the sale

Chinese aviation officials concede that courting foreign airlines could be a more daunting task than convincing the EU regulator.

Gu said the threshold for a plane series to be commercially successful is deliveries of 1,000 units or more.

The C919 may have some appeal for regional airlines in China, but it has little attraction to those outside the region who are committed to either Boeing or Airbus

“Technical success is no guarantee of marketability. Even for the A320 and 737, the cash cows for Airbus and Boeing, some variants never sold well,” he said. “Commercial success is rare.”

John Grant, founder of London-based JG Aviation Consultants, said airlines have yet to develop interest in the C919.

“The C919 may have some appeal for regional airlines in China, but it has little attraction to those outside the region who are committed to either Boeing or Airbus,” he said.

“For airlines, the choice of aircraft is a fundamental consideration, the most important cost element. They require complete confidence in an aircraft type and its performance, operational support and flexibility across a range of sector lengths.”

Li, the aviation analyst, said the rarity of the C919 means higher flying and service costs compared to mainstream models.

“In the foreseeable future, only Comac and a smaller number of third-party entities can service the jet, but Airbus and Boeing run sprawling maintenance networks worldwide,” he said. “Comac may need time to establish service centres in Europe.”

Some analysts also pointed to shortcomings in the C919’s design vis-a-vis its competitors from more seasoned manufacturers.

Shukor Yusof, founder of Endau Analytics in Singapore, said there are concerns over C919’s comparatively high use of steel over composite materials, which could make it heavier and less fuel-efficient than Western models of the same class.

The C919 is 12 per cent composite by weight, significantly less than the Airbus A350’s 50 per cent.

Analysts also point to C919’s conservative design that is less efficient than the A320neo, also from Airbus.

I would not be surprised if a major airline outside China places an order within the next 24 months

But neither these nor other disparities with established rivals has dampened Comac’s drive to poach their business, and the manufacturer has begun an all-out effort to sell prospective clients on its plane.

“Some airlines in Asia are already deliberating on it as a potential addition to their fleets. Asia is more likely to be C919’s proving ground than Europe. I would not be surprised if a major airline outside China places an order within the next 24 months,” Yusof said.

“Overall, the aircraft flies well, is quiet and offers value for money.”

In Europe, executives with Irish budget carrier Ryanair have repeatedly affirmed their interest in the Chinese jet in the years since the company signed a memorandum of understanding with Comac in 2011.

OAG’s Patel said it was “good timing” for the C919 to try nibbling away at the two heavyweights’ market share, as Airbus has to contend with a production bottleneck as carriers reassess the safety of the Boeing 737.

“European airlines are retiring some of their fleet and the assessment, negotiation and procurement of new [planes] take time. The C919 is on their radar,” he said.

Comac has attempted to make such a transition as smooth as possible, with intentional design decisions to model the C919 after the A320 to ensure its jet is marketable and easy to operate.

The cockpit layout is directly inspired by the A320, and a pilot can manoeuvre the plane using a sidestick controller. Cabin crew qualified to operate on the A320 and Boeing 737 will only need three days of training to work on the C919, according to Comac.

“The consideration is [for the C919] to feel instantly familiar, so foreign pilots can adapt quickly,” said Jie of the Shanghai Airworthiness Certification Centre.

China Eastern pilot Xiao Cheng said steering the plane was like “driving a car with automatic transmission.” He has accrued 500 hours of flight time in the Chinese jet.

“The sidestick is integrated with multiple controls and is as responsive as the steering wheel of a car. The pilot can get all critical information at a glance from the five 15-inch LCD screens mounted across the cockpit,” Xiao said. “It’s very hi-tech.”

A plane of Theseus?

In this scenario, the C919’s engine, landing gear and avionics – all sourced from Western suppliers, including GE and Honeywell of the US and France’s Safran – would be progressively swapped out for indigenous alternatives in a long, arduous process of intensive research and development.

Jie admitted it would be many years before this conversion could be completed, as changes to major components would require recertification. Analysts also say a higher proportion of domestically produced parts may affect the plane’s overseas recognition and sales.

“For any country, aviation technology is the cachet of R&D and so strategic it will not be exported or shared. You can’t buy it or swap your market for tech transfers. There are few countries in the world capable of developing and launching aircraft or engines,” Gu said.

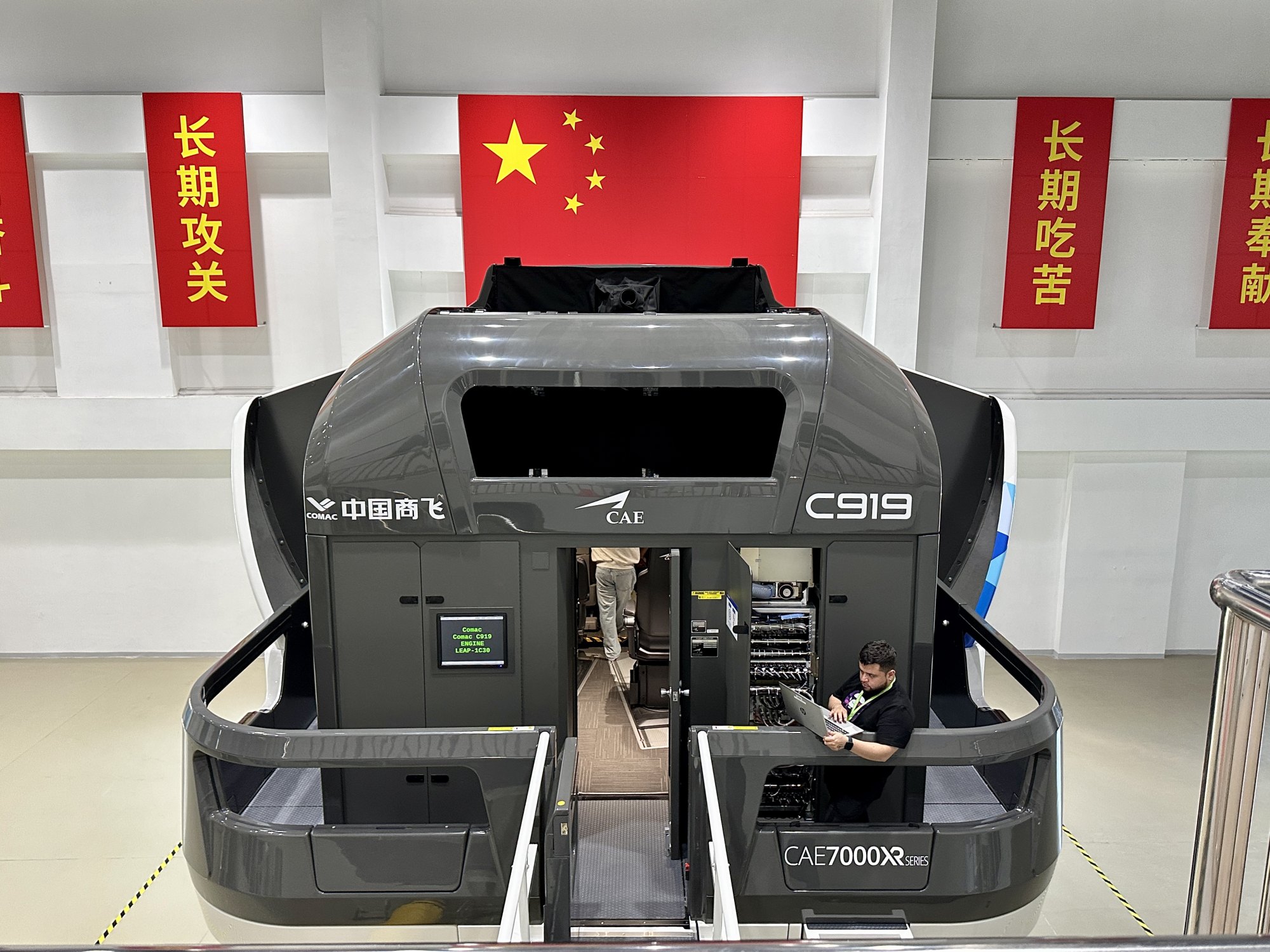

“We have for decades relied on perseverance. There are slogans plastered at C919’s assembly facility at Comac – ‘long-term efforts for long-term research’ and ‘long-term work for long-term contributions’ – and these words sum up our fighting spirit.”