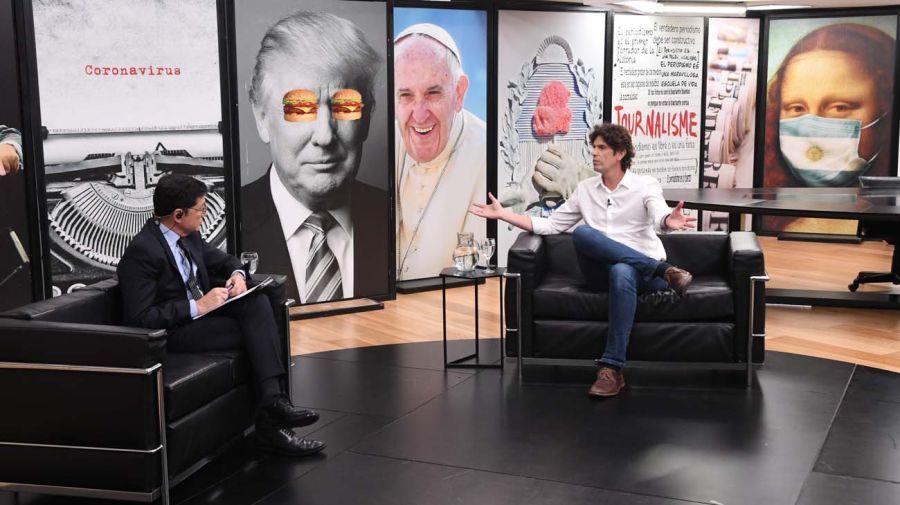

Martín Lousteau, chairman of the Unión Cívica Radical and senator representing Buenos Aires City, was harshly criticised by the business world and the national government for voting against President Javier Milei’s DNU emergency mega-decree, which he affirms to be unconstitutional.

Expressing his concern about President Milei’s insensitively authoritarian bias and the democratic regress of a segment of society, the 53-year-old analyses the economic variables of the first few months of the libertarian administration, voicing disbelief in the supposed rebound effect.

Lousteau commits himself to working towards a centrist alternative, equidistant from the libertarian and Kirchnerite extremes.

After your vote against [President Milei’s] DNU emergency mega-decree, Argentina’s richest man [CEO and founder of MercadoLibre] Marcos Galperin criticised you personally. Why do you think he did that and could you reply?

I don’t know what he said.

That you are on the side of Kirchnerism.

A vote against that DNU is a vote for the Constitution. No constitutional scholar says that the DNU is constitutional and we need to take that into account when judging it. What would I say to Galperin? He founded a global enterprise emulating many companies born in the United States and many of those who admire the United States do so because of the rule of law, which prevails there and because it has a Constitution which nobody escapes. Plus he decided to live in Uruguay, because, I would calculate among other things, it has no polarisation and because the rule of law also prevails there. So I believe that the only road for Argentina to develop is to follow the Constitution and follow the law. There is a paradox here. In other countries, when somebody tells you that something is illegal, end of argument. But in Argentina, when somebody points out the illegality, we start saying: ‘Well yes, but I’m doing this because my intentions are good and it’s only for a short while.’

Or a law which must be reformed.

Those who go on and on talking about the importance of the rule of law and the institutions for development, when it comes to implementing the things they’d like to do, they couldn’t care less about the rule of law. I think that is a serious error. Things must be done within the law.

In the Latinobarómetro survey of democratic values, 30 percent of Argentines responded that they would be inclined to accept a non-democratic government if the economy works. Again, the end justifies the means and hence dictatorships.

There is a sort of democratic regress, in particular among the youngest. Within that Latinobarómetro survey Argentina scores much better than the rest of Latin America but it is true that this trend is starting among the young. In the case of Argentina it seems to me easier to find a reason why this is happening among youth. If you are 30 in Argentina and per capita GDP has not grown for the last 14 years, this means that since you were 16 and started entering adult life, Argentina has been stagnant so you say: ‘This is not working out.’ That forms part of the motive for seeking other alternatives.

You’ve been ambassador to the United States. What do you think of having a businessman like Gerardo Werthein as ambassador?

The United States has a very particular culture and, at least when I was there during the Donald Trump period, I saw that it is important for an ambassador to the United States, beyond what is needed by any ambassador, that US government agencies know that the envoy has a good relationship with his president, that they are on WhatsApp terms. And since it is a culture where the business world is highly valued, that seems a positive attribute to me.

Another ambassadorial candidate, Shimon Axel Wahnish picked for Israel, had a rough time in the Senate Appointments Committee. Do you imagine that there could also be problems with other ambassadorial appointments who are political appointments?

I was with Axel Wahnish the other Friday and before that I met up with the Foreign Minister [Diana Mondino] because there is another problem there. The issue is not the ambassador but the presidential mention of moving the Argentine Embassy to Jerusalem. There is a 1980 United Nations Security Council resolution which does not recommend that – indeed, it says that it should not be done. It rejects the installation of embassies in Jerusalem, asking for diplomatic missions to be withdrawn from that place. In Argentina’s case, defying it would be to defy a UN resolution so that tomorrow Britain, or any other country could say: ‘We don’t recognise any resolutions’ and that would be harmful to Argentine claims to the Malvinas. That’s the issue. Yesterday I met the Foreign minister and she told me that no decision would be taken which would jeopardise the solidity of Argentine claims to the Malvinas, which overcomes the clashes on this point as far as I’m concerned.

What do you think of President Javier Milei’s Supreme Court nominations, federal judge Ariel Lijo and constitutional scholar Manuel García-Mansilla, and do you think that they could clinch the two-thirds Senate majority which any Court justice needs to be elected?

Firstly, as we have already seen in the past with [Attorney-General nominee Daniel] Rafecas, I’m waiting for the government to send the documents formally saying: ‘These are the candidates,’ because in so many other cases there have been leaks which afterwards do not translate into reality. Just as versions of a new ‘omnibus’ law are in circulation yet when one asks if it is the definitive version, they tell you: “No, there is no formal definitive version.” So first I want to wait and see what is happening.

Secondly, it is important that the missing member and the replacement of [retiring justice Juan Carlos] Maqueda give the Court a gender perspective which it lacks – there should be two women. That is my opinion.

As for the candidates, we will await the process because I’m no expert in this area but luckily Supreme Court candidates have a prior hearing with challenges and we will see everything which emerges in that process. In the case of both candidates, I repeat, if it gets that far because we still have nothing.

Does the hypothesis about a deal between Kirchnerism and the libertarians, so that Lijo can obtain that two-thirds majority, seem plausible to you?

That forms part of this government’s constant contradictions. When I voted against the DNU, they told me: “You voted with Kirchnerism.” No, Kirchnerism made a sudden discovery of the Constitution and principles, whereas I voted in favour of what I have always believed. The government’s contradiction is that if they want the nominations approved, they’re going to have to convince Kirchnerism and vote with Kirchnerism.

You have said that Milei is a president who attacks his own vice-president [Victoria Villarruel]. She disagreed with not increasing the pay of parliamentarians, arguing that it needed to be high so that seats could be held by persons who are not politically powerful, millionaires or narcos. Do you agree that parliamentary pay should be high? And can you imagine a vice-president heading the Senate with a different agenda to the President?

No. I believe that the vice-president heads the Senate with the government agenda but also that she has a better eye as to what are the restrictions because she knows that others think differently. She knows that La Libertad Avanza has only seven senators. But the President, who is far more authoritarian in that sense, does not accept any differences or even debate. He has a hard time understanding the restrictions of reality and the need for dialogue and debate. And in the face of frustration, his chosen reaction is to go immediately on the attack. He does it with journalists, television hosts and artists and he does it with politicians, thus creating a complex microclimate because, among other things, it is starting to induce a kind of self-censorship. People start thinking: ‘I believe this, but is paying the price of saying it worthwhile?’ I’m not afraid of leaders with an authoritarian streak as long as society is healthy and not afraid. When the contrary starts to happen, I get worried and think that I have to draw a line, saying that there is no need to be afraid to talk.

Do you see a real economic plan on the march or just austerity?

I see an obsession. I see an obsessed president with a very biassed outlook on what the economy is. He is obsessed with the fiscal deficit and thinks that this will resolve all Argentina’s problems. Argentina’s problem is the poor quality of spending, which is why we have a deficit, and because we spend badly, we need to spend more. I believe that there is a sort of reductionism where many economists get stuck in the following logical sequence: ‘Is it true that we have inflation because we print money?’ Yes. ‘And is it true that we print money because of our deficit?’ Yes. And then they stop there. The question they should be asking themselves is: ‘Why do we have a deficit?’ Because the political world has never known how to resolve the distributive tussle by saying: ‘This is a priority and this isn’t.’ I remember when [former leftist Uruguayan president José] Pepe Mujica took office, he told the [Legislative] Assembly: “Our top priority is education and next comes education and then third education.” And the assembly burst into applause. When the applause ended, he then said: “Now if we’re going to give a huge ‘yes’ to education, we are going to have to agree on what we should be saying to everything else.” That is what Argentine politicians have not known how to do and I do not see any change today in that. I do not see any agreement as to where to spend and where not although the people are demanding that. The people have the correct agenda but Milei is pushing it through badly…

[Milei] is obsessed with the deficit so in order to find a transitory fix for the deficit, he is causing a disaster for the real economy and the social fabric while not improving the state. He is using inflation to lower the deficit so that the bad spending is not corrected, just reduced, while the good spending is also reduced. Is he carrying out a profound state reform so that Argentina can grow again? In my opinion, not.

I do not see any plan in agreement with what the people are asking for. I see cuts in health, education, pensions and infrastructure. At what point do these questions lead to a higher standard of living and more growth? In my opinion, they don’t. If he manages the state like that, Argentina will find it very hard to grow.

Could it be that he believes, with a vision stemming more from private enterprise, that if you lower spending, you will create pressures for them to be used well, because when you have less, you have to use those funds more carefully?

That might be his vision but it is one which is making society pay an enormous cost for a political learning process which should be moving in a different direction. Curiously enough, when Milei exaggerates, because he exaggerates in almost all questions of public policy, and society and many affected sectors react in fear, there arises an enormous margin to be able to begin negotiations.

The CGT is now starting to say that it agrees with labour reform. It’s the time to do it because that part of the DNU is stuck in the courtrooms. Cristina Fernández de Kirchner has said the same. There’s room to do it. We all agree that the state cannot continue as it is. Without a state we’re going nowhere. And it is true that he believes the market to be the only disciplinary mechanism because, as he says, he doesn’t believe in the state. Contradictions. He announces a plan of scholastic assistance for lower middle-class sectors to send their children to private schools at a time when a whole bunch of people are having to pull their children out of school. The announcement arrives late and the implementation later still. Now an overwhelming majority of private schools are already receiving subsidies to pay their teachers. So now there are subsidies for teachers and some families who need them due to Milei’s abrupt decision but it is a double subsidy. Meanwhile he is withdrawing the Fondo de Incentivo Docente booster for teacher pay and saying that public education is indoctrination while he goes off and brainwashes his old school and says, for example, that UBA Buenos Aires University’s Economics Faculty is also indoctrination despite [his own Economy Minister Luis] Caputo and [Buenos Aires Province Governor Axel] Kicillof being products. He looks down on public education when his own idol [economist Friedrich] Hayek was schooled at the University of Vienna, which is public, and he’s given classes at the London School of Economics, where I did my Masters, which is also public. So there is a sort of bad faith or ideological falsity or manipulation or ignorance or a failure to think problems through or I don’t know what to call it. And so that aggressive president inclined to excesses who does not stop to think things through and who does not like debate, is going to have a much harder time finding the correct solutions.

You used the word “excesses.” Might they not be an invariable characteristic of Argentine politics with Milei simply the paroxysm of a trend which has been going on for a long time in Argentina?

Maybe. Going over the top in Argentina is always a response to previous failures. So instead of charting a path for the future, presidents tend to say: ‘I am not what went before.’ So they try to put that across with communication, as is happening currently. They need to do it in a far more exaggerated, hyperbolic way.

At a business event the President said that he was going ahead with “the biggest austerity programme of humanity,” which was celebrated by the auditorium. Can you imagine, as they do, a V-shaped growth curve or does that seem delirious to you?

I cannot imagine it but I hope I’m wrong. I’d love to see Argentina growing again. I don’t think it will happen because economies grow when people can consume more, when businessmen decide to invest more, when the state spends more or when there are more exports.

You were Ambassador to the United States and know the credit organisations there. Can you imagine the possibility of the International Monetary Fund or the US Treasury making an extra loan of US$15 billion for an earlier exit from capital controls?

I’d have a hard time thinking that for various reasons. Firstly, because from the conversations I’ve had, the United States has a certain ambiguity or dilemma – I don’t know what to call it – with Milei. On the one hand, Milei says everything they want to hear with a total, almost unthinking alignment, which is something any power wants to hear, in particular from a country which carries weight within the region like Argentina. That is a problem because we also have our own agenda. I remember, when [Barack] Obama came to Argentina, arguing with the [Mauricio] Macri government, which was saying: “What can we give him?” I said: “We have to follow our own agenda; if we are trying to resolve other people’s problems, we’re off to a bad start.” Obama came to Argentina as a counterbalance to previously visiting Cuba so we had to make the most of that for ourselves. Gringos use the term “Shopping list” – what is ours? They see that we are aligning ourselves with them without asking for anything in exchange. On the other hand, they have their doubts about the nature of Milei’s leadership, about his personal characteristics, about the social problems and the sustainability of certain reforms. So they have a stance…

Ambivalent.

Apart from that, you have to factor in their elections and there are doubts about the sustainability of the plan while we have a very big commitment to the IMF with a plan which did not work out and which wrongfooted the Fund itself. So I imagine Milei to continue flirting with the United States with almost no agenda of his own, as is his wont, while seeking more goodwill from them. But it does not come cheap for the United States to make such a deep commitment to releasing so many fresh funds, and far less for an adventure of dollarisation without consensus or even conversation.

You have said: “Milei is bringing cruelty into fashion” by “accumulating power and instilling fear.” Is there any fear of an attack against the democratic pact of the last 40 years?

At this stage we have to ask ourselves if behind the slogans of liberty there does not lurk an authoritarian streak which does not admit dissent and which uses all available means to silence alternative voices. In today’s society, where there are many media to make different thinking visible but also to punish it, this triggers fear in many people, making them think twice before saying what they think. That undermines our democratic agreements.

What do you think of the constant contrast with Kirchnerism made by the national government and the criticism you received for resembling Kirchnerism by voting against the DNU? Are Kirchnerism and La Libertad Avanza alike in their populism?

They are linked in many ways. Firstly, I believe that they are two anachronistic economic visions, one from the 1970s and the other from the final decades of the 19th century. And secondly, I believe that both have authoritarian streaks and that part of their bias is using the media at hand to punish those who think differently. In the case of Milei, the achievement is much greater than anything I have seen before with much more intensity and much more obsession and with cruelty, as Martín Kohan says.

Let us explore the issue of the renewal of the Unión Cívica Radical. When you voted against the DNU, Senator Pablo Blanco was the only Radical to join you while Maximiliano Abad abstained.

Edith Terenzi was another Radical senator voting against.

What were your prior conversations with your senatorial colleagues and what were your feelings after the vote in the days which followed?

Firstly, everybody said in private that the DNU was unconstitutional so the question becomes why they could not uphold that position. There might be three reasons for that. Firstly, that they genuinely convinced themselves that it was constitutional.

So they changed their minds.

They changed their minds but genuinely. The second reason, convenience. My governor needs some things done and I don’t want to confront him. Thirdly, fear, as we were discussing beforehand. If anybody had been genuinely convinced that the DNU was constitutional, they would have defended it as such on the house floor. Because when there is an issue with so much rating that it hogs attention, everybody wants to talk and this time nobody does. Pablo Blanco and I spoke against. Then Víctor Zimmerman, who sits for Chaco, a province with problems, followed by Rodolfo Suárez, the former governor of Mendoza, another province which we rule. But then nobody wanted to speak and that struck my attention greatly.

You have said that within the Unión Cívica Radical there is agreement over the agenda of change for which the people voted but they do not share the forms, for example, sending the laws as a package and not separately. Independently of formal questions, is there a Radical majority in support of most of the content of the ‘omnibus’ law and the DNU?

We are in agreement that there must be reforms and I could enumerate which. We disagree with some of the reforms which the President is trying to implement for various reasons. In some cases, because they seem irrelevant to us and not the hub of the problem and in others because they seem tinged with very important corporate interests. So they are not a priority or they are moving in the opposite direction to where we should be heading. And in other cases because while it seems good to eliminate the deformities of the state, the truth is that this is not the way to do it. Does going against public education and public health leave us a better state? I disagree.

I want to delve into the question of whether Juntos por el Cambio still exists and the relationship between PRO and La Libertad Avanza, and if it is correct to say that if Milei does well, PRO will become the UCEDÉ of Carlos Menem, and if badly, the FREPASO of Fernando De la Rúa.

Firstly, I see that the main figures of PRO have either entered the government or are working very hard to do so. I see it with [Security Minister] Patricia Bullrich and with Caputo and then I see it when I listen to [Diego] Santilli or [María Eugenia] Vidal. It seems to me that they are disowning the things they said before. Once again the rule of law, not emergency decrees, and the importance of institutions. So I see them as a sort of symbiotic process.

And where is that symbiotic process heading? Who will eat who?

There are expectations on both sides. PRO wants Milei to do more or less well and he needs them without diluting their identity. Firstly, the government does not think that this is going to happen and on the other hand, does not want to dilute its own identity because, as we were discussing before, Milei has a very dogmatic vision of things, so I see that as stuck. What seems problematic to me is that I do not see PRO constructing or making references to its own identity but instead they are being copycats so it seems to me that they are losing identity. All that is left of PRO are the governors, Mayor Jorge Macri in the City of Buenos Aires, ‘Nacho’ Torres [Chubut] and Rogelio Frigerio [Entre Ríos].

How do you imagine that this relationship could evolve and who would be diluted?

I don’t know because I also hear dissatisfied voices within PRO. They are a minority because PRO is not such a broad or democratic party but there are voices like [Buenos Aires City ex-mayor] Horacio Rodríguez Larreta. We’ll see in next year’s midterms how much those voices count, depending on how Argentina is doing. But for now I see PRO diluting its identity and looking increasingly like La Libertad Avanza.

You were at the March 24 march. What did you feel was happening there?

I think two things conjugated. The first on the government side, I do not know whether out of conviction but there are sectors of Argentine society with anti-democratic convictions or tendencies who evidently did not manifest them before but who are now coming out into the open because they see daylight. And although not seen before, now they are with many other people going spontaneously to the plaza. And once again the government gave its own tone to these differences, castigating, insulting, attacking and mocking them. And that is worrying in terms of our democratic co-existence so I saw more people than before. It was important that the Radicals were present. They always are but they have a different visibility because, as I was saying before, [Raul] Alfonsín decided to place both sides on trial while not viewing them equally because state terrorism is another thing altogether. Today we have the backlash of people who manifestly deny state terrorism or minimising it. Whereas Alfonsín did not make the trials a party banner but a social banner, when Kirchnerism revived the trials, which was a good thing, they transformed a consensus which permeated society into a partisan banner.

They appropriated

something.

And in the face of that appropriation many people also react against that political grouping. It is a major paradox that they set in motion a backlash by appropriating from a partisan viewpoint. That’s why it seemed very important to me that the Unión Cívica Radical should make itself visible there in the plaza.

Production: Melody Acosta Rizza & Sol Bacigalupo.