Migrants. Drugs. Imports that pose a threat to the viability of industries in the United States.

U.S. President-elect Donald Trump would like to stop them all from entering the U.S. from Mexico.

The lengths to which he is willing to go to get what he wants could significantly define Mexico’s relationship with the United States during the four years of the second Trump presidency.

Trump’s stated plans to carry out “the largest deportation operation in American history” and renegotiate the USMCA free trade pact are also likely to have a profound impact on Mexico if they come to fruition.

Claudia Sheinbaum, sworn in as Mexico’s first female president five weeks ago, will become the third Mexican president to deal with soon-to-be President Trump, who is well-known for his unpredictability.

Sheinbaum’s capacity, and that of other Mexican officials, to effectively manage the relationship with the second Trump administration, and defend Mexico’s interests under the almost inevitable pressure to come, will be crucial to the success of her government, and the country as a whole.

In her initial remarks on Trump’s victory, she sought to downplay the risk he will pose to Mexico as president, telling Mexicans both here and in the United States that “there is no reason for concern.”

“… There will be a good relationship with the United States. I’m sure about that,” Sheinbaum said.

While there is no certainty that the Trump administration will execute plans precisely as they were described during the presidential election campaign — perhaps it is even unlikely — there is still significant concern in Mexico about how the country will be affected by them.

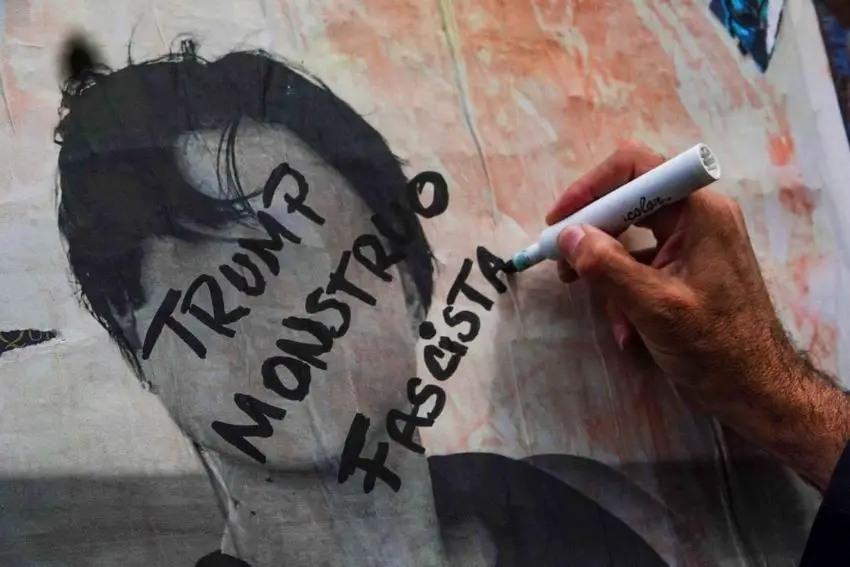

While he is a polarizing — and popular — figure in the United States, Trump is widely disliked in Mexico, in large part due to the various disparaging remarks he has made about the country and its people.

With the commencement of a second Trump administration just 2 1/2 months away, let’s take a closer look at how some of the plans of the 47th U.S. president could affect Mexico.

Trump’s border security plan and Mexico’s potential role in it

During a victory speech in Florida in the early hours of Wednesday morning, Trump once again pledged to “fix our borders.”

He made stopping illegal immigration to the United States via Mexico a central platform of his third presidential bid, and during his campaign outlined plans to hire an additional 10,000 border agents, deploy the military to the border, expand the border wall and implement immigration policies even stricter than those of his first term.

The success of his plan, however, could ultimately hinge on Mexico’s willingness and capacity to stop migrants from reaching the Mexico-United States border.

Trump is well aware of that, prompting him on the eve of the U.S. presidential election to issue a threat to “immediately” impose a 25% tariff on all Mexican exports to the United States if the government of Mexico doesn’t stop what he called an “onslaught” of criminals (read migrants) and drugs to the U.S.

He used a tariff threat to his advantage during his first term as president, pledging to impose 5% duties on all Mexican exports if the Mexican government didn’t do more to stem migration to the United States.

The two countries subsequently reached a deal that averted the blanket tariffs and resulted in Mexico deploying federal security force members to both its southern and northern border.

“We got Mexico to give us 28,000 soldiers free of charge, no cost, and we had the greatest border in history,” Trump said at a rally in 2023.

Will he have similar success in getting Mexico to effectively become a second “border wall” during his second term as president? According to a former head of Mexico’s National Immigration Institute, his chances are good.

“We’ve seen what Trump does. What he is proposing is the 3.0 version of the same increased pressures on Mexico,” Tonatiuh Guillén told The New York Times.

“Mexico gave in to the pressures back then, and the question is whether Mexico will give in again. I think the likelihood it will is high,” he said.

Trump on Monday said his tariff plan has “a 100% chance of working” because if Mexico — the world’s biggest exporter to the United States — doesn’t respond to a 25% tariff threat, he’ll increase it to 50%, 75% or even 100% if need be.

While he has continued to claim that the United States is being “invaded” by migrants, illegal crossings into the U.S. have in fact declined significantly since U.S. President Joe Biden enforced a new border policy in early June.

How would mass deportations from the US affect Mexico?

In addition to stopping migrants coming into the United States, Trump wants to get large numbers of those already there out of the country.

Reuters reported on Wednesday that Trump is “expected to mobilize agencies across the U.S. government to help him deport record numbers of immigrants, building on efforts in his first term to tap all available resources and pressure so-called ‘sanctuary’ jurisdictions to cooperate, according to six former Trump officials and allies.”

There are an estimated 4 million undocumented Mexican migrants in the United States that could face expulsion under Trump’s mass deportation plan.

“Mexico could also find itself pressured, as in the past, to accept Venezuelans, Nicaraguans or Cubans, who are sometimes unable to be deported to their origin countries for diplomatic reasons,” the New York Times reported.

The deportation of large numbers of Mexicans could have a considerable impact on the amount of money Mexico receives in remittances (more than US $63 million in 2023), and completely cut off a much-needed source of income for many Mexican families.

Furthermore, the Mexican economy could struggle to provide jobs for large numbers of deportees who suddenly find themselves in Mexico after being uprooted from their lives in the United States. Unemployment would inevitably increase if the economy can’t integrate them all.

Needless to say, the deportation of large numbers of migrants from the United States — many of whom work in low-paid but essential jobs — would also have a major impact on the U.S. economy.

“It would be an economic disaster for America and Americans,” said Zeke Hernández, an economics professor at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania.

“It’s not just the immigrants who would be harmed, but we, the people of America, would be economically harmed,” he said.

How far could Trump go to combat Mexican cartels?

Both “criminals” and “drugs” are what Mexico needs to stop crossing the border into the U.S. if it is to avoid tariffs on its exports, according to the threat Trump made on Monday.

While he put the onus on Mexico with that remark, Trump has indicated that his future government could take additional action of its own to stem the northward flow of drugs such as cocaine, methamphetamine and fentanyl, a powerful synthetic opioid largely responsible for the drug overdose crisis in the United States in recent years.

In August, he pledged to “impose the death penalty on major drug dealers and traffickers.”

In July, he said that military strikes against Mexicans cartels such as the powerful Sinaloa Cartel, and their drug-manufacturing facilities, were “absolutely” an option.

“Mexico’s going to have to straighten it out really fast or the answer is ‘absolutely,’” Trump told Fox News.

During his first term as president, Trump floated the idea of firing missiles into Mexico to combat cartels, according to his former Secretary of Defense Mark Esper.

Other Republican party figures, such as Senator Lindsey Graham, have advocated the use of the United States military in Mexico to combat cartels that smuggle fentanyl and other drugs into the U.S.

Former president Andrés Manuel López Obrador categorically rejected the idea that the United States military could be used in Mexico, and in 2019 declined an offer from Trump to help Mexico combat organized crime after an attack on members of an extended Mormon family in northern Mexico that killed three women and six children.

If the United States was to unilaterally use its military against Mexican cartels, it would be “extremely damaging” for the U.S.-Mexico relationship, according to the head of the Inter-American Dialogue, Rebecca Bill Chavez, who was quoted by The New York Times.

She said that such a move — which would not necessarily result in less narcotics reaching the United States — could jeopardize all cooperation between Mexico and the U.S., including on trade.

Sheinbaum is continuing to use the Mexican military for law enforcement against cartels, but it is virtually unthinkable that she would consent to U.S. military action against the criminal organizations, no matter how determined she is to combat high levels of violent crime in Mexico.

In response to a tariff threat from Trump, the Sheinbaum administration could conceivably argue that Mexico is already making significant efforts to stop illegal drugs crossing into the United States.

Federal officials made that argument during the previous term of government, with former foreign affairs minister and current Economy Minister Marcelo Ebrard describing Mexico as “the United States’ main ally in the fight against fentanyl.”

Indeed, the Mexican government seized a record amount of fentanyl during former President Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s six-year term, an achievement acknowledged by U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken earlier this year.

Trump’s other tariff threats

During the election campaign, Trump also made repeated threats to impose hefty tariffs on vehicles made in Mexico. His threats appeared mainly directed at Chinese automakers that are planning to open plants in Mexico, such as BYD, but in September he pledged to “put a 100% tariff on every single car coming across the Mexican border.”

Last month, he issued the following warning to Chinese automakers planning to establish a presence in Mexico, and export cars to the United States (which BYD, for one, has said it has no intention of doing):

“I will impose whatever tariffs are required — 100%, 200%, 1,000% — they’re not going to sell any cars into the United States with those plants,” Trump said, referring to facilities that have not yet been built.

As president, he also said he would “seek strong new protections against transshipment so that China and other countries cannot smuggle their products and auto parts into the United States tax-free through Mexico to the detriment of our workers and our supply chains.”

U.S. tariffs on vehicles made in Mexico would of course be detrimental to Mexico’s vast auto sector, whose exports primarily go to the United States. Tariffs specifically targeted at vehicles made in Mexico by Chinese automakers could cause such companies to reconsider their plans to invest in Mexico, even as they publicly say they have no intention to export to the U.S.

Cancellation of Chinese auto plant plans would, of course, mean that Mexico doesn’t receive the investment and associated benefits it otherwise would.

Mexico could also come under pressure from the Trump administration to limit its trade and investment dealings with China and Chinese companies.

There are signs that it is already yielding to U.S. pressure.

While federal officials have insisted that Chinese investment is welcome in Mexico, Reuters reported in April that pressure from United States authorities had led the Mexican government to refuse to offer incentives to Chinese electric vehicle manufacturers planning to invest in Mexico.

Furthermore, the Sheinbaum administration appears determined to reduce reliance on Chinese imports. Deputy Economy Minister for Foreign Trade Luis Rosendo Gutiérrez Romano told The Wall Street Journal last month that the government wants U.S. automakers and semiconductor manufacturers with a presence in Mexico, as well as large aerospace and electronics companies, to substitute some goods and components made in China as well as Malaysia, Vietnam and Taiwan.

Such an initiative would presumably be welcomed by a U.S. administration led by Trump, who initiated a trade war with China during his first term as president and looks set to be even tougher on the East Asian economic powerhouse during his second term.

Willingness to cooperate with the United States on efforts to reduce reliance on China and bolster the North American economy — as the Sheinbaum administration has demonstrated in its first month in office — could help Mexico to get a more favorable outcome when the USMCA is renegotiated in 2026.

Trump said last month that he would have “a lot of fun,” renegotiating the three-way pact as he seeks to improve — from a United States’ perspective — what he described as already “a great deal.”

Reuters: Sheinbaum has ‘room to negotiate’

Reuters reported on Wednesday that Mexico “must maneuver carefully” given that Trump will soon return to the White House, but added that President Sheinbaum “still has room to negotiate and soften the impact on trade, migration and security.”

Citing analysts, the news agency said that after a likely deterioration of relations with the U.S. in the short term, “Mexico has some leverage, particularly on migration, that could help dilute some of Trump’s pledges in areas such as trade and security.”

Mariana Campero, senior associate with the CSIS Americas Program, told Reuters that Sheinbaum could say to the Trump administration, “‘Okay, Mexico can take [deported] Mexican nationals back, but you won’t impose the tariffs.’”

The Mexican government, Reuters said, could also ask U.S. companies that benefit from the USMCA to lobby the Trump administration against tariffs on Mexican exports.

Leeway to negotiate with the next U.S. government could also be assisted by Trump’s transactional tendencies — his apparent, or alleged, willingness to enter into quid pro quos.

By Mexico News Daily chief staff writer Peter Davies ([email protected])